There is a fairly decent overview of the contract situation faced by entertainers in Korea over in today’s Joongang Ilbo. Using the lawsuit Dong Bang Shin Gi (aka TVXQ) has filed against SM Entertainment as the peg, the article looks at the long and onerous contracts that most entertainers in Korea have to have, especially singers.

As you have probably heard, on July 31, three members of DBSG filed suit against its management company, claiming their contract is unfair. DBSG is one of SME’s most popular bands these days, and is doing especially well in Japan, where they recently played two nights in the Tokyo Dome. The band’s complaints were mostly the same things we have heard over and over again in Korea over the years — their contracts are too long, their contracts do not pay enough, the penalties for leaving the management company are too severe, the performers do not have enough control over their own careers, the performers are not paid enough (probably the biggest issue).

I do not want to get into the details of DBSG’s particular case. That is something for the Korean courts to decide. But I do think that cases like these bring up a much bigger point.

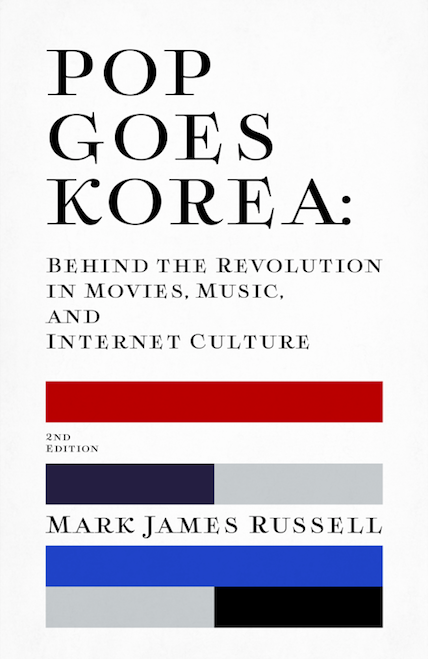

Arguing about the “fairness” of idol contracts — how many years should they be, how much should the performers be paid, etc. — misses the big point. I am tempted to call it “Rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic,” but that is probably a bit harsh — after all, the Korean entertainment industry is showing few signs of sinking any time soon. It is more like arguing about what kind of pain reliever is best for a critically ill patient. That is, such talk deals mostly with the symptoms of the disease and misses out entirely on the causes.

Korea’s pop idols are not paid poorly and overcontrolled because the management companies are evil. The management companies are just doing their best within the current system. And judging by the long list of big stars who have emerged from Korea’s music system over the years, they are apparently doing something right.

The trouble is, Korea’s music system itself, which is very resource-intensive and very top-down (like far too much of the Korean economy in general). Because the burden of developing stars and marketing them falls solely on the music companies, it takes a huge amount of money to create new stars. The biggest companies have over 50 performers (mostly young people) in training at a time, taking dance classes, singing classes, learning how to act like stars, and usually living in company housing, eating food paid for by the company, being driven everywhere by the company. All this adds up pretty quickly.

So when a band gets paid pennies for an album sale, you have to remember that the performers spent years in training before they earned any money, and that for each performer earning money and doing well, there are many other aspiring young people who never make it, but who nonetheless burn through company money. How many hopefuls does each company have for each performer who makes it? Five? Ten? I do not know, but it is big enough.

The real problem (as I argue in my book, POP GOES KOREA) is the lack of diversity in Korea’s music business, in particular the lack of a live music scene. In most countries, live music is the core, the heart. Young people pick up instruments and play in their parents’ garages or wherever. Some get good enough to play in clubs. A few get good enough to put out albums (or MP3s or whatever). A very few make money. Basically, the cost and inconvenience of developing acts falls on the wanna-be performers. By the time they get to the music labels, a lot of the winnowing and development has already happened.

Even in Japan, where J-Pop is big business, you have J-Rock and jazz and a fairly wide range of choices. And choices drive competition, when reduces the stranglehold that music companies otherwise might have.

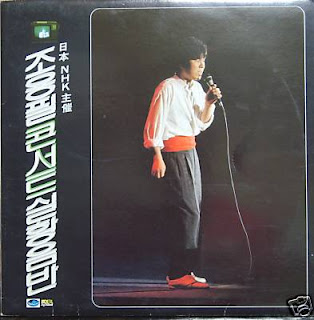

Strangely, Korea used to have a great live music scene. It was a long time ago, but back in the 1960s and 1970s, most of the big performers had a live music background, whether playing on the US Army bases around the country or playing the live clubs of Myeong-dong or wherever. Even in the 1980s, as Korea’s music scene turned more poppy and synthesized (and saccharine), there was still a live foundation most of the acts had — Cho Yong-pil, Shin Hae-chul, Jo Sung-mo, and the like were all live performers first.

But in the early 1990s, the scene began to change, especially with the coming of Seo Taiji. Even though Seo Taiji wrote his songs (well, mostly) and performed them himself, he typically performed them prerecorded, with The Boyz dancing away furiously beside him. It was the formula that Korea’s music companies would use to create their boy- and girl-bands. And soon the manufactured dance bands came fast and furious. Within a few years, they dominated the TV music shows, Mnet, and the like.

For a generation of young people in Korea, being a “star” has meant being a dancer first, a pretty face and perhaps a singer. Very few young people pick up a guitar with dreams of making it big. Sure, plenty of kids play music, for any number of reasons. But few harbor serious dreams of using the guitar (or whatever) to become rock stars.

And as long as the live music scene is not a viable route to becoming a star in Korea, the local music scene will remain dominated by the music labels and manufactured pop music.

The funny thing is, for all the talk of the dominating power of the music companies, the truth is they are actually very weak. They are merely responding to the economics they are given. If young people were to choose different music, the whole system would fall apart. If playing in Hongdae became a route to fame and fortune, then the system would have to change. But as long as Korean young people show no interest in anything but K-Pop, all they will be given is K-Pop. And the system will not really change.